Dandy, The

Regions: UK

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of The Dandy and its companion comic paper, The Beano, in British popular culture of the twentieth century. For generations of readers, these two titles, launched in 1937 and 1938, were virtually synonymous with the phrase “British comics.” Although neither is well known outside the UK, save among expatriates, their audience recognize instantly their peculiar blend of lunacy and irreverence as quintessentially British.

At the time of The Dandy’s launch (as The Dandy Comic) in 1937, publisher D.C. Thompson had established its ascendancy in the field of boys’ adventure-story papers with its “Big Five” weeklies, Adventure, The Rover, The Wizard, The Skipper, and The Hotspur. In 1936, the Thompson chain’s Scottish Sunday Post newspaper introduced a “Fun Section” supplement, which launched two extremely popular comic strips, “Oor Wullie” and “The Broons.” Inspired by that success, Thompson’s head of children’s publications, R.D. Low, laid plans for a second “Big Five” comprising weekly comic papers.The Dandy Comic was the first to appear, in December 1937, followed by The Beano Comic in 1938 and The Magic Comic in 1939. The outbreak of war in the fall of 1939 halted the expansion at three titles and eventually reduced the number to two when wartime paper restrictions forced the cancellation of The Magic Comic early in 1941.

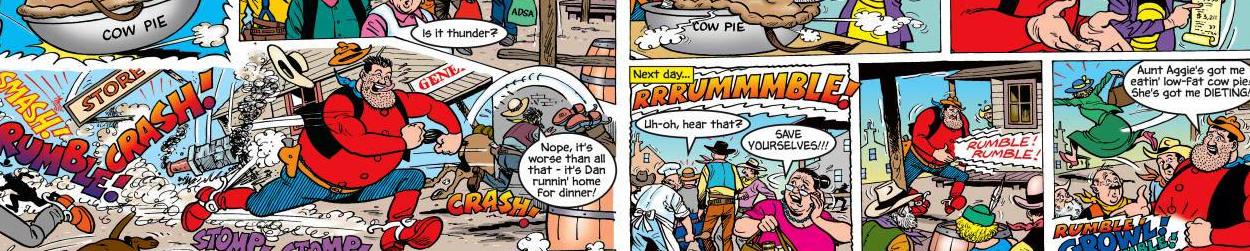

Prior to 1937, the British comics market was dominated by Amalgamated Press, whose monochrome “penny blacks” and more upmarket “tupenny coloureds” separated word and image, featuring rows of illustrations above text captions. In several ways, The Dandy Comic imitated the established model: its cheap, black-and-white newsprint pages were given some oomph by coloured covers, and it offered a similar range of genres, from funny animals to westerns to stories featuring popular movie stars, as Amalgamated’s Film Fun (1920-1947) did.However, while several strips followed the familiar picture-strip model, most of The Dandy’s humour strips,including“Desperate Dan,”“Keyhole Kate,” and “Korky the Cat,” abandoned prose captions in favour of speech balloons, in imitation of the comic strips appearing in newspapers, melding word and image to produce a more fluid and rapidly-paced style of comedy. Prose fiction also featured heavily in the comic early on, filling nearly half of the debut issue’s 28 pages.

The Dandy was an immediate success, outselling even the most popular of the “Big Five,” The Wizard. While The Magic Comic was one of many victims of wartime paper rationing, which required publishers to reduce their paper consumption by 60%, both The Dandy and The Beano remained in print throughout the war, albeit reduced to fortnightly publication and eventually a skimpy 10 pages. Although paper was a precious wartime commodity, morale on the home front was also of importance, and The Dandy justified its continuing presence by presenting its young readers with heavy doses of patriotism along with reassuring and comforting stories of life during wartime. Korky, Kate, and even the nominally American Desperate Dan joined the war effort, downing German planes and sinking U-boats amid notices reminding young readers to save waste paper. A new strip, “Addie and Hermy, the Nasty Nazis,” offered a mocking depiction of Adolf Hitler and his lieutenant, Hermann Göring, as a pair of incompetents constantly in search of their next meal.

As rationing was gradually phased out in the 1950s, the British comics industry entered what is generally regarded as its golden age, during which the UK was one of the largest producers and consumers of comics in the world. In 1950, sales of The Dandy peaked at 2 million copies per week, and a staggering 102 million issues were purchased in that year. The ascendancy of comic papers was achieved in part at the expense of the older story papers, some of which were themselves converted into comics over the course of the 1950s and 1960s. The Dandy stopped running its prose-adventure features in 1955, but many of those serialized stories continued to appear in the comic strip format. Among the most popular of these was the Lassie-inspired Black Bob, a prose serial featuring a Scottish Border Collie begun in The Dandy in 1944, adapted as a comic strip in Thompson’s The Weekly News two years later, then again as a strip in The Dandy in 1956, where it ran intermittently until 1982.

The Dandy and The Beano remained the market leaders throughout the 1960s and 1970s, but the overall British comics market was in a long decline. The Beano emerged, gradually, then dramatically, as the more popular of the two companion papers, but both began seeking new revenue streams: licensing their characters, accepting paid advertising, and engaging in headline-grabbing publicity stunts, such as having Desperate Dan disappear for several weeks in 1997 and timing his return to coincide with the comic’s 60th anniversary. New formats were tried as well, such as the Dandy Comic Library, a monthly publication featuring a single character in a longer story than the flagship comic’s anthology format allowed. The gravity of the drop in circulation is indicated by the radical, and ultimately failed, 2007 makeover that brought into being The Dandy Xtreme, a fortnightly children’s magazine focusing on celebrities and video games, in which the familiar comic strips were initially relegated to a Dandy Comix insert. A near-return to form in 2010 failed to secure the comic’s future in print, and the final issue circulated as The Dandy marked its 75th anniversary in December 2012, since which time the title has remained in existence online via the dandy.com website and in the form of the hardcover Dandy Annual, a Christmas institution whose popularity grew even as sales of the weekly comic dwindled.

— Brian Patton

Further Reading

- Carpenter, Kevin. Penny Dreadfuls and Comics: English Periodicals for Children from Victorian Times to the Present Day. : Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983.

- Chapman, James. British Comics: A Cultural History. London: Reaktion Books, 2011.

- Gravett, Paul and Peter Stanbury. Great British Comics: Celebrating a Century of Ripping Yarns and Wizard Wheezes. London, Aurum, 2006.

- Riches, Christopher, ed. The Art and History of the Dandy: 75 Years of Biffs, Bangs and Banana Skins. Glasgow: Waverly Books, 2012.

- Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels. London: Phaidon Press, 1996.