Revolver

Regions: UK

Despite its very brief life, Revolver is remembered today as one of Britain’s most innovative, if confusing, mainstream publications of its time. Owned by Fleetway, publisher of the mythical 2000AD magazine’s second life, the monthly was launched in July 1990 only to be canceled after seven issues in January 1991.

There are at least three identifiable lines of thematic convergence at stake in Revolver. The first would be the late 1980s, early 1990s New Wave trend that counted with a few other titles, from both major and smaller publishers, such as Escape, Pssst!, Deadline, Blast!, Strip, Toxic, and its Fleetway sister-title, Crisis. Most of these were anthology titles that rose under the perception of the “maturation” of comics within the English-speaking world, stemming from the aftereffects of mainstream milestones Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. These anthologies produced edgy, adult content, sometimes mirroring current events, and promoting aesthetic innovations, trying to expand genres, styles and readership. Internationally speaking, it could be integrated in a context in which North-American Raw and Spanish Madriz played their part. Still, Revolver was, in spite of its bizarreness, less experimental that those other magazines.

Secondly, and because Revolver’s mission was not, like Crisis, to follow North American genres, it looked into national culture, tapping into the Britpop music scene, quoting the 1960s (“the ’90s are the ’60s upside down”, its first issue proclaims) and the subsequent “Cool Britannia” attitude. As such, it mimicked some of the colorful, high-end music magazines of its time, producing a psychedelic, positive attitude rehashing of British colloquialisms.

Finally, it gave its authors more creative leeway, although the magazine’s editorial direction was not coherent, as Revolver was a mix bag of genres and formal approaches. Despite the hype and the signing tours, it had a quick downfall (yet another trend in the aforementioned titles), the lion’s share being its disastrous sales. Its better paper stock did not help as it meant a higher price.

Possibly the two most remembered works it published were Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy’s “Rogan Gosh” and Grant Morrison and Rian Hughes’ take on Dan Dare, simply titled “Dare.” “Rogan Gosh” was the only complete story published in the magazine, a mind-bending, angsty, acid trip through India-style comics, mixing spirituality, sex and a Kipling lookalike. Taking a ride in the so-called British Invasion in the U.S., it would be published by Vertigo in 1994 in a “prestige” format, acquiring a second life. As for “Dare,” somewhat like Alan Moore had done with Miracleman and Frank Miller with Batman, this was a revamping of Frank Hampson’s 1950 character. However, instead of a full-fledged bleak take or a metatextual reinvention, Morrison and Hughes created a version in which the characters and the setting became a veiled representation of Thatcherite Britain, maintaining Dare’s ultimate ethical, heroic role. With the magazine’s cancellation, it was completed in Crisis and re-issued as a 4 comic book series by Monster Comics.

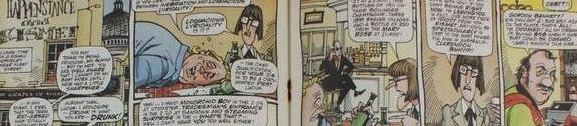

Along these two series, there were a number of other flagship works, amongst which “Purple Days,” an unfinished and largely forgotten biopic via psychedelic spiritual journey, à la Carlos Castañeda, of Jimi Hendrix, by music journalist Charles Shaar Murray and Floyd Hughes. The absurd “Happenstance and Kismet” was written by Paul Neary and drawn by Steve Parkhouse, and to some extent it seemed to tap into the same premise that Parkhouse had tried out with Alan Moore with The Bojeffries Saga: a humorous strip about an unlikely hero in a number of odd, fantastic adventures with matching characters, also left unfinished. Julie Hollingsworth participated with “Dire Streets,” a sort of soapish series about the convoluted relationships life or young urbanites, and Shaky Kane had a running two-pager called “Pinhead Nation,” a sort of weird dream diary of the namesake character.

Apart from the recurring team of authors, Revolver published a number of one-off cartoon strips and short stories, with which it filled its two special issues, The Revolver Halloween Special and Crisis Presents… The Revolver Romance Special. Considering how Fleetway was interested in fostering new talent, and even trying out new properties, through short installments in 2000 AD and its other titles, its “mature lines” included, the artists found in these shorter pieces were either already famous or would become household names: Sean Phillips, Glenn Fabry, Al Davison, D’Israeli and Ian Edgington, Mark Millar, Garth Ennis, Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham, John Smith, Si Spenser and Ed Bagwell, brothers Warren and Gary Pleece, are some of those names. Nonetheless, with very few exceptions, their participation in the short-lived magazine would not be their most significant work.

Ultimately, the demise of Revolver, and perhaps other titles, was due both to commercial and editorial problems. On the one hand, it had been a tentative conquest of a territory that did not exist. The change of a truly mass market (children’s comics) into a niche market (the future “graphic novel” one) had not coalesced at the time, so the lower sales were not only considered unprofitable as unacceptable. On the other hand, the befuddling hodgepodge of very different work did not help, and it is a very different thing to proclaim oneself “mature” and to actually provide a well-conceived, organized, and better contextualized work of long form comics–something which Revolver did not provide.

— Pedro Moura

See also: 2000 A.D.; Dan Dare; Hampson, Frank; Toxic!

Further Reading

- Berridge, Ed. “Pop Goes Art! The Story of British Adult Comics”. Parts Two “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” and Three “Too Much Too Young”. Judge Dredd Megazine nos. 276-277, pp. 16-22 and 18-24. Print.

- Sabin, Roger (1993). Adult Comics: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. Print.