Gemma Bovery

Regions: UK

Gemma Bovery is the title that arguably introduced Posy Simmonds to a larger readership, thanks to the frank handling of its themes – national identity, unbridled passion versus control of one’s emotions, the confusion between life and art – within a dramatic framework. Published daily in the pages of The Guardian, it was collected into one volume in 1999, after which it was met with critical success, privileged exposure, and immediate translations. Loosely based on Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, it follows a similar plot, to the extent in which the female protagonist’s desires and projections take over her waking life, leading her towards a doomed end.

The book centres on British illustrator Gemma, who moves to Bailleville, a small fictitious village in Normandy, France, with her husband Charles Bovery, a restorer. It is told retrospectively after her death by Raymond Joubert, a well-read, local baker smitten with Gemma. We follow his attempt in piecing Gemma’s life together from a number of sources. Not only does Joubert use his own recollections of her arrival in Bailleville and her dealings with the locals, as he resorts to documents such as letters, newspaper clippings and even Gemma’s own diary, some volumes of which he pilfered under Charles’ nose. Through this textual reconstruction, mingling Joubert’s typed text and Gemma’s handwriting, we enter her complicated love life, which involves Charles’ manipulative first wife, Gemma’s old lover, food critic Patrick, and her new local interest, the affluent Hervé. It is Joubert who finds numerous parallels between the lives of Gemma and Flaubert’s famous character, colouring the retelling of her fate. Time and again, it is Joubert who points out to Gemma, and us in the process, to the common plot points of both stories.

As typical in a comedy of manners, Gemma’s imagined idyllic, romantic French country life clashes with the plainly boring reality. The protagonist’s ennui is barely ameliorated by her trysts and fleeting interests, and she plunges into ever more complicated problems with her lovers and debts, just like her literary counterpart. This geometry ends with Gemma’s unexpected, accidental death, which can be seen as an oddly tragicomic outcome.

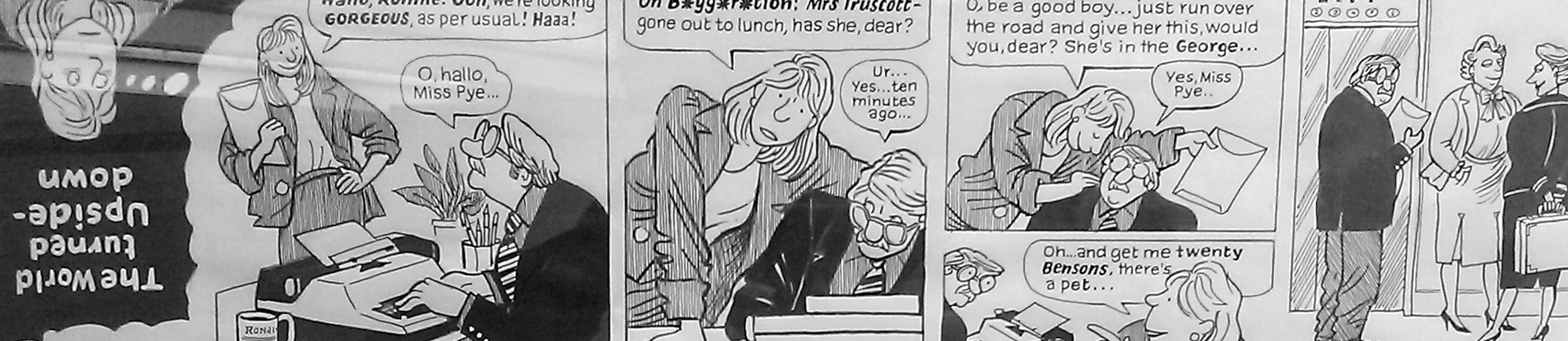

Apart from the diverse textual tracks, the sometimes conflicting, sometimes complementary accounts of the events, the book is spotted with recipes, Victorian-styled illustrations, maps, notes and object lists, expanding thus one’s expectations of comics’ usual vocabulary and structure, and augmenting its “literary” penchant. Moreover, it brings texture to the books’ realism and a bold richness to the peculiar storytelling techniques, traits which Posy Simmonds has largely explored throughout her work.

— Pedro Moura

See also: Simmonds, Posy

Further Reading

- Miodrag, Hannah (2013), Comics and Language: Reimagining Critical Discourse on the Form. University Press of Mississippi.