Comics in France, Belgium & Switzerland

Regions: Belgium, France, Switzerland

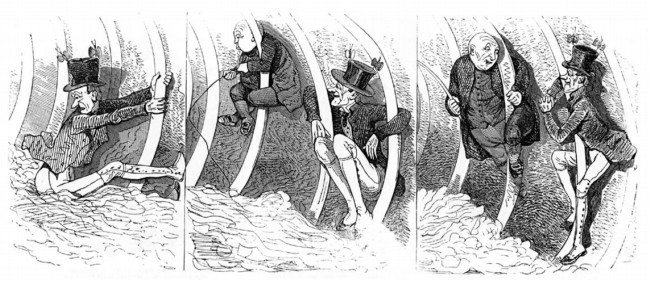

In a sense, it could be argued that the Genevan artist Rodophe Töpffer (1799-1846), generally considered the founding father of modern Francophone (and European) comics, invented most of the features of modern comics storytelling. His work was a radical innovation to the tradition of the single broadsheet, poorly colored and heavily captioned, woodcut storytelling featuring moral or didactic stories and legends that had been circulating throughout Europe in previous centuries. Although maintaining the distinction between panels and captions, Töpffer did create a new type of word and image interaction, which are in his pages truly hybridized. Töpffer also claimed cultural legitimacy for his “drawn literature,” which was very appreciated by representatives of the literary establishment such as Goethe. Besides, he also conceived his work no longer in broadsheet or magazine format, but as independent books, sold on subscription, while displaying a strong sense of social critique and commitment (his books can be read as a romantic critique of contemporary society). Finally, Töpffer proved also an excellent theoretician of drawing itself, the cognitive and narrative possibilities of which he defended in comparison to the then brand new medium of photography. Well circulated and even plagiarized in France, Töpffer’s work was not influential enough to act as a counterweight to what was the dominant model of visual storytelling in 19th Century France: the gag strips in the weekly and monthly magazines, strongly influenced by the booming industry of political cartooning in the press. Important visual artists like Gustave Doré explored the multipanel technique, either with captions or as wordless pantomimes, to tell stories, some very short, some already in book length format. They were not labeled comics (in French: “bandes dessinées,” drawn strips) but in retrospect are clear instances of it. The major example of late 19th Century comics in France is however Christophe’s La Famille Fenouillard (serialized since 1889, reissued in book format from 1893 on), a mild parody of French provincial culture.

Under the influence of the tremendous success of Christophe and the new US newspaper strips, the Francophone market launched several local versions of comics series built around recurrent characters and serialized in newspapers or weeklies. None of these comics uses speech or thought balloons, and the split between panels and captions (which are typeset, and not handwritten as in the case of Töpffer, who made use of the visual analogy of drawing and handwriting) explains the less dynamic form of these works, which were also strongly differentiated among gender, social, and ideological lines (with often a direct control of either the Church or the State). In the first decades of the 20th Century, the most interesting series are the female Bécassine (1905), a nickname for “fool,” serialized in a weekly for upper middle class young girls, and the more popular, sometimes anarchist comics of three male antiheroes, Les Pieds nickelés (1908, literally: “The Lazy Bumps”). Word balloons was initiated by the French Alain Saint-Ogan in Zig et Puce (1925), an adventure strip with and for boys, and the Belgian Hergé (Georges Remi).

It was Hergé who proved most successful in developing a homegrown type of the serialized adventure comic, with a clearly recognizable style focusing on the legibility of the drawings as well as that of storyworld and storyline. Via the clever marketing of Tintin books, Hergé’s success soon crossed national borders. In his case, the book release was more than just a present offered to a good-selling author targeting both a popular and a more affordable audience, it became the horizon that shaped the properties of the installment format: the serialized adventures were streamlined to enter a standardized format of a 62 pages hardback album format, and this two-layered model became the Francophone standard from the 1960s onwards. Hergé elaborated the Clear Line style, which on the one hand simplified drawing (no shadows or hatching lines, only monochrome color zones clearly separated by contour lines) and on the other hand provided the images with an exceptional sense of rhythm (within each panel as well as between panels). By doing so, he produced a perfect match between visual transparency and narrative clarity, that fitted well the ideological boy-scout values of the series based on honesty, friendship, and healthy entertainment.

The tremendous success of Tintin magazine, one of the many comics weeklies that emerged after WWII and which serialized the adventures of Tintin, made Clear Line the absolute standard for the new comics industry in French. This comics market was dominated by the competition by two schools: the Tintin or “Brussels” school, featuring Hergé but also authors such as Jacques Martin and characterized by visual sobriety and ideological conservatism, and the Spirou or “Marcinelle” school, featuring among others Jijé and Franquin (the creator of Gaston, antihero avant-la-lettre and clear antipod of Tintin) and experimenting with a more spontaneous and humoristic drawing style. Both schools shaped the Franco-Belgian style, which was all over the place in Francophone comics during the “golden age” between 1945 and 1965. Though made in Belgium, Tintin and Spirou were actually made for the French market, as can be noticed in their settings as well as their props (the mansion Tintin lives in is not a Belgian but a French one), and they served as a model to most Francophone authors working in that period.

From the 1960s onwards, the Franco-Belgian style was no longer in tune with the spirit of the times. In 1959 a Parisian publisher, Dargaud, launched the weekly Pilote, which serialized among others the adventures of Asterix and become the laboratory of many young artists who developed more adult, if not underground forms of comics, in Paris and elsewhere. These new comics were part of a larger countercultural movement that eventually produced the May 68 revolution in Paris. In the beginning, Pilote mainly aimed at offering a profound renewal of traditional comics, with more room for the individual style of previously studio artists, but very soon the authors of the magazine started looking for new forms and formats (yet always sticking to the A4 album format). One of the pivotal figures of this movement is Jean Giraud, aka Moebius, co-founder of the publishing company Les Humanoïdes Associés (1974) and the magazine Métal Hurlant (1975). Author of various masterpieces of experimental SF such as Arzach, Moebius was also involved in the American Heavy Metal, which did not follow the strong editorial line of the French original.

The creation of the journal (A Suivre) in 1978 was the synthesis of the Franco-Belgian tradition and the avant-garde tendencies in the slipstream of Pilote and its underground heirs. It proposed a literary version of comics, not in the sense of the US “Classics Illustrated” but in the spirit of visual storytelling for sophisticated audiences with a literary background. (A Suivre) invented a new publication format, based on the serialization of often unusually long visual novels prepublished in long chapters (the literary notion of “chapter” was totally new in comics) and containing explicit or implicit references to literary storytelling techniques. It was published by the leading classic comic publisher Casterman (home to the Adventures of Tintin) and incorporated many novelties of the previous decade, rejecting some major staples of the comics industry, such as the use of color (the price to pay for the absence of page-limit) and the obligation to serialize successful one-shots. (A Suivre), which lasted until 1997, has been the test bed for countless authors of modern bande dessinée, among them Schuiten and Peeters, creators of The Dark Cities, a work that radically reinvents the notion of series as well as that of comics universe.

By the end of the century, after the collapse of the magazine market and the complete shift from prepublication formats to book format and one-shots, a new phase emerged, with on the one hand the integration of conventional comics in multimedia franchise policies and on the other hand a return to more experimental styles. The French publishing house L’Association and the Belgian Frémok supported these new voices, in certain cases with exceptional commercial triumph (Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis is the best examples of it). In all cases, however, the new experimental bande dessinée is also the result of a steadily globalizing market, and the dialogue between the alternative Francophone and the American graphic novel has become part of everyday comics life in France and Belgium. The progressive vanishing of the traditional A4 album format in the newer comics is a clear symptom of this influence.

— Jan Baetens

Further Reading:

- Bart Beaty, Unpopular Culture: Transforming the European Comic Book in the 1990s (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2007).

- Thierry Groensteen, The System of Comics. Translated by Bart Beaty (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

- Ann Miller, Reading Bande Dessinée: Critical Approaches to French-language Comic Strip (Bristol : Intellect, 2008).

- Ann Miller and Bart Beaty, eds. The French Comics Theory Reader (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014).

- Thierry Smolderen, The Origins of Comics: From William Hogarth to Winsor McCay. Translated by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).