Comics in Australia

Regions: Australia

While there is some scholarship on comics in Australia, and the history of Australian comics, this field of visual culture remains relatively unexamined. In the latter half of the twentieth century, comics such as the long-running Ginger Meggs by Jimmy Bancks, the Barry Humphries inspired “Barry Mackenzie” character (though drawn by the English artist Nicholas Garland for Private Eye, itself an English book series) are perhaps more familiar household names. In more recent decades, however, independent and online comics websites have frequently worked as umbrella sites for a number of Australian comic artists. Among these projects, names such as Shaun Tan, and Pat Grant, for example, have received relatively widespread, and sustained attention.

Running alongside the production of comics art, there is a rich, and long-standing tradition in Australia, of satirical and political cartoons, such as Andrew Marlton’s “First Dog on the Moon” series, and Kudelka Cartoons by artist Jon Kudelka. One of the earliest examples of works in this tradition, which also utilized a comics proto-form, was Melbourne Punch magazine, which was founded in 1855. Closely following the layout and format of London Punch, which was established some years earlier in 1841, Melbourne Punch was made up of strips characterized by formulaic narratives and naïve humor.

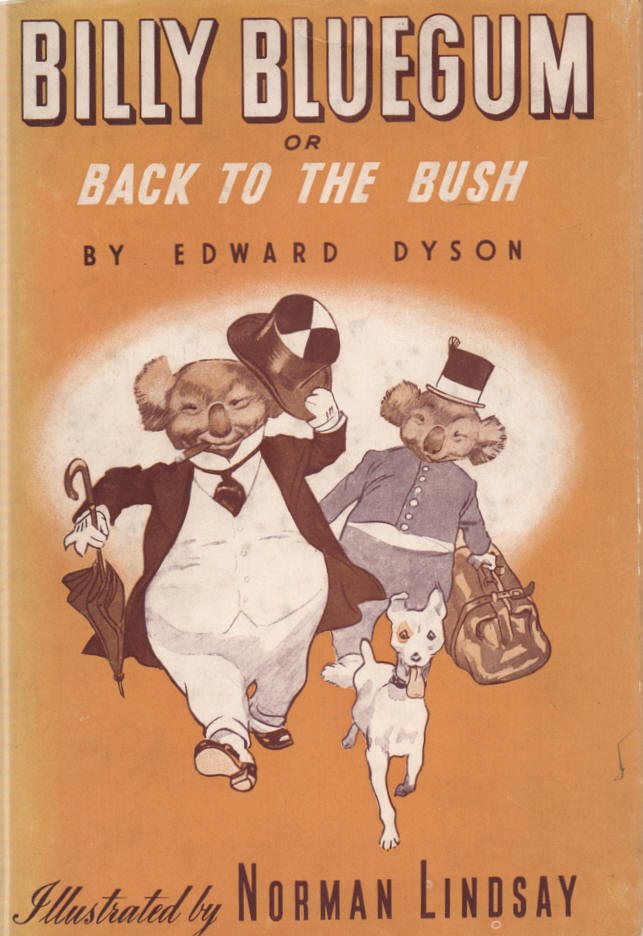

Norman Lindsay, perhaps best known for his illustrations in The Magic Pudding, worked with Edward Dyson to create what might arguably be considered the first Australian comic strip. Billy Bluegum, or, Back to the Bush, was originally published in 1907 as a serial in The Lone Hand (The National Australian Monthly). Billy Bluegum was introduced, rather lengthily, as an “energetic bear who has been brought to the city, is inspired with a mission to go forth and confer the inestimable blessings of Civilization upon the bears of the Bush, taking with him a magical bag labelled “Public Loans,” which enables him to scatter blessings freely.” Lindsay’s beautifully executed drawings are markedly distinct from earlier illustrative comics works in publications such as Melbourne Punch.

In 1908, the comic Vumps (with its eponymous character Joe Vumps) was published in Sydney, in what became a one-off production (although it was planned for weekly issue). Subtitled, “Pure Australian Fun,” the promoters had promised that the comics “matter will be clean and distinctively Australian,” with no place for the “pernicious sensational literature with disfigures the English and American so-called comic papers” (24 July 1908, Hebrew Standard of Australasia). Despite the quality of artistic work in the first volume by Hal Gye, Mick Paul, Ambrose Dyson, Claude Marquet, and illustrations accompanying a story by Henry Lawson (one of Australia’s pre-eminent writer at the time), production on Vumps ceased after extremely low sales of the first issue.

The next comics publication, the Comic Australian, was much more successful, with 80 issues produced between 1911 and 1913. Featuring the work of poet Hugh McCrae, among a wide variety of visual artists, this production is significant for the introduction of “stock” characters of a distinctly “Australian” bent, such as bushrangers, Indigenous Australians, and swagmen, as well as animals such as koalas, snakes, and kangaroos.

This work helped to establish a tradition of incorporating animal characters in Australian comics, exemplified by later comics such as Noel Cook’s Kokey Koala and his Magic Button, which was published in Sydney by Offset Printing between 1947 and 1955, as well as Skippy the Bush Kangaroo, published in the 1970s, written and illustrated by Keith Chatto.

Australia experienced a suburban boom in the 1920s, and this provided plenty of fodder for new comics creations, as well as an audience to consume them. Originally produced as You and Me in Smith’s Weekly in 1920, this strip by Stan Cross initially featured only two characters, “Pott” and “Whalesteeth,” before changing its aspect to a domestic setting. Known as one of the longest-running strips to be drawn by a single artist, the comics artist Jim Russell (a staff member at Smith’s Weekly) assumed production of this strip in 1939, which featured the Potts family, and re-named it The Potts, elevating the significance of “Australian” family life into the national comics imaginary. Russell drew this strip until his death in 2001, alongside which there was The Potts Annual, published in Melbourne by The Sun News-Pictorial (Herald and Weekly Times) from 1952 to 1960. The strip was syndicated in the United States between 1957 and 1962, under the title Uncle Dick. Stan Cross also created a number of short-run comics, such as “Smith’s Vaudevillians” (1928-39); “Tickle Twins” (1929); and “Dad and Dave in Snake Gully” (1938).

In November 1921, the Sunday Sun published a four-page color comic supplement entitled “Sunbeams,” accompanied by the statement that far from being a “rehash of English and American work,” the supplement would “embody a feature absolutely new to Australian journalism – designed, drawn and printed by Australians,” and including work by DH Souter, and JC Bancks. As noted, the latter was the creator of Ginger Meggs, first known under the name Us Fellers, focusing on the daily adventures of the eponymous character with his family, friends, and nemeses.

The artist Moira Bertram, born in Sydney, was among the few female comics creators in the 1940s and 50s. At the young age of 14, Bertram created her first comic strip, Jo and Her Magic Cloak, about a Broadway dancer whose magic cloak could take her anywhere she pleased. This strip is notable for placing a female at the centre, rather than the periphery, of the main narrative. Bertram then went on to self-publish The Red Prince (1947), and Red Finnegan (1949), for which her sister, Kathleen, completed the lettering, as well as a number of other works.

That same year of 1947 also saw the production of another comic that focused on group almost ignored in Australian comics to date. Pacific Pictorial Comics published by A. Lyall Lush, focused on the history of the peoples of the Pacific Ocean by means of text below each comic frame. One story, drawn by Rosamund Stokes, called “Fun at Cockatoo Island,” was set in the North Island of New Zealand, and another, “Pogl and Namja” depicted the story to two Aboriginal children who lived on a mission station in Central Australia. Pacific Pictorial Comics was relatively successful, with publication running for two years until 1949.

The 1950s saw a decline in the Australian comics industry, in part because of steep increases in the cost of newsprint, which had begun its climb after World War II, and later, because of increased public scrutiny on the “moral” impacts of comics—a fear imported from the United States with the imposition of a Comics Code Authority. The following decade, perhaps unsurprisingly, saw the end of original production of previously popular comics such as The Phantom Commando and The Panther, although comics zines became increasingly available such as the first Australian “comiczine,” Down Under, which was published in Sydney by John Ryan in December 1964. Comics became increasingly diversified from the 1980s onwards, and today there are significant online comics repositories, such as Cardigan Comics, a site that hosts a number of comics, as well as individual artist pages.

Killeroo, created by Darren Close in 2003, continues the tradition of creating anthropomorphic animals in Australian cartoons, with Killeroo as the leader of an outback biker gang in 1980s Australia. Close’s influence from American superhero comics is evident in this action-packed comic. Along with the permutations on the Australian superhero genre such as those depicted in Phosphorescent Comics stories, and the Cyclone Comics universe, comics in Australia have evolved along diverse trajectories. For example, Pat Grant’s debut graphic novel Blue (2012) evokes an everyday yet haunting urban setting in which members of a ‘blue’ community experience racism and narrated through a remembered past. Nicki Greenberg’s graphic adaptations of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Hamlet, among other works, has received widespread acclaim for her inventive style. Shaun Tan’s works, with their focus on themes such as depression, migration, invasion, and adventures into the unknown, have also attracted critical and popular acclaim.

— Golnar Nabizadeh

Further Reading:

- Bancks, James Charles. Ginger Meggs Annual. Sydney: Shakespeare Head Press, c.1952

- Bertram, Moira. Flameman: Genie of the Sun. Sydney: Sungravure, 1946.

- Dyson, Edward and Norman Lindsay. Billy Bluegum or Back to the Bush. Sydney: Shepard Press, 1947.

- Gordon, Ian. “The symbol of a nation: Ginger Meggs and Australian national identity” Journal of Australian Studies 16:34, 1-14. 1992.

- Grant, Pat. Blue. Portland: Top Shelf. 2012.

- Tan, Shaun. The Arrival. Melbourne: Hachette Press, 2006.

- Wheelahan, Paul. The Panther. Camberwell: Buzz Productions, 2001-2002.